Packrafting the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge: A 275-mile traverse in the Brooks Range

- Tim Kelley

- Nov 12, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Jan 10

Why packraft the Refuge?: Alaska's Arctic National Wildlife Refuge encompasses a massive area at the eastern end of the Brooks Range between Gates of the Arctic National Park and the U.S.-Canadian border. The Brooks Range is often cited as one of the landscapes that propelled the development of packrafts due to thousands of navigable miles of wilderness rivers complemented by excellent tundra walking. Situated north of both the Arctic Circle and treeline, the Refuge offers expansive views, ranging from craigy alpine peaks along the spine of the Brooks Range to the sweeping plains of the Arctic coast. The Refuge is an important home for some of North America's most prominent megafauna, including all 3 bear species endemic to North America, as well as the massive Porcupine Caribou Herd, numbering over 200,000 animals. The region is also the home of the Inupiaq and Gwich'in people who live in adjacent communities such as Kaktovik and Arctic Village, and rely on the ecological well-being of the Refuge to maintain their traditional subsistence practices. The Refuge's status is threatened by oil and gas interests, which have long sought to roll back the Refuge or open the area to extraction. In 2025, the coastal plain, a crucial habitat for many arctic species, was opened for drilling.

ROUTE OVERVIEW

There are countless ways to travel through the Refuge. After many hours combing over maps, chatting with friends, and measuring mileages, we settled on this route (depicted below) for two primary reasons:

1) Cost: We wanted to do the traverse as economically as possible by foregoing any charter flights. Not only would this help minimize our costs, but it would also help us whittle down dozens of options to only those between a clear start and end point. By starting on the Dalton Highway, we could take advantage of a van shuttle service from Fairbanks. By ending on the Arctic Ocean in Kaktovik, we could return to Fairbanks on a scheduled flight.

2) Maximizing Paddling: Part of the joy of packrafting in the Brooks Range is that the walking is excellent. That being said, we knew with a route of this length, we would appreciate every opportunity we had to get off our feet and into our boats. With the Dalton to Kaktovik parameters in mind, I just went about looking for the connection that would yield the most time floating. While many of the North Slope rivers run due north to the Arctic Ocean, the somewhat northeastern courses of the Atigun, the Ribdon's South Fork, the Upper Ivishak, and Saddlerochit helped them stand out as segments to build a route around.

Alternatives Exits: I've included a couple of route variations in the above map to highlight alternative exits back to the Dalton Highway. These exits on the Ivishak and Ribdon would make for great routes in their own right or could serve as options to bail from the traverse if time or circumstance dictates.

Season/Flows:

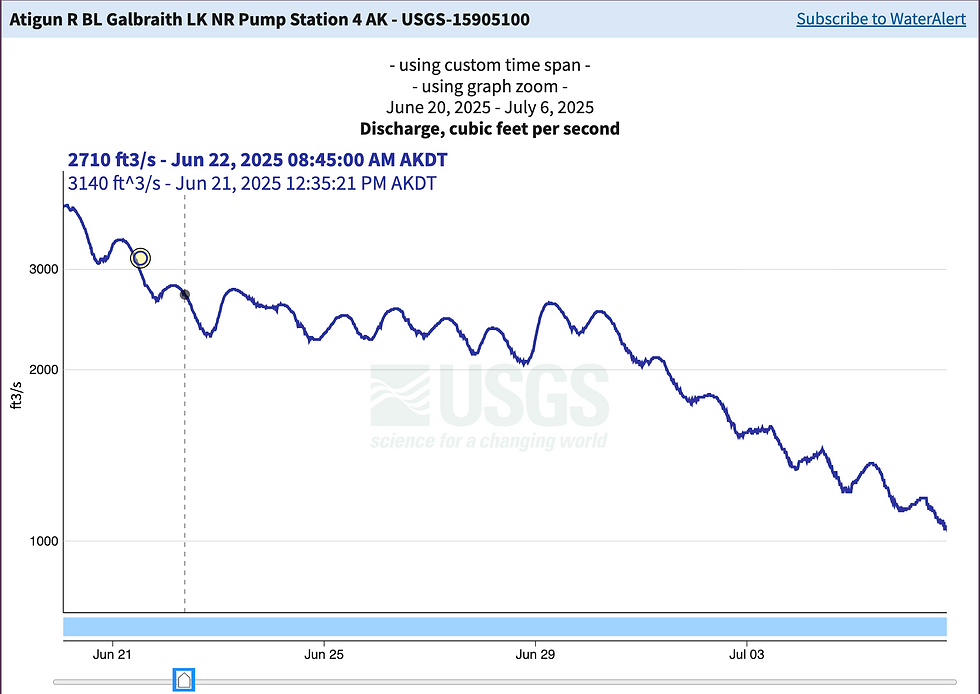

Many parties prefer a late summer trip in the Refuge to maximize berry season, miss the worst of the mosquitoes, reduce the amount of lingering snow encountered in the alpine, and minimize the amount of auefis (permanent river ice) along the banks. That being said, we were intentional about starting our traverse in late June to coincide with the end of the spring melt, which allowed us to begin all our paddling segments closer to each river's headwaters. While the mainstem rivers are paddleable throughout the summer, later trips should expect to do more walking and less paddling than what is depicted in the embedded map. Specifically, our timing on the South Fork of the Ribdon, Ivishak, and Marsh Fork likely allowed floating higher in the drainage than we could have late in the season. By the time we reached the Saddlerochit on day 12, all of the snow in the watershed was gone, and the river was paddleable but lower than expected. While there are very few river gauges in the Brooks range, the gauge on the Atigun River should help assess a general trend in snowmelt. Below is the gauge reading during the time frame of our trip, with the reading at the dashed line denoting the time of our launch on the Atigun.

ROUTE DESCRIPTION

Paddle: Atigun River, III-IV

The Atigun River is a convenient starting point for many Refuge traverses. While there are lots of potential drop-off points along the Dalton Highway, starting a multi-week trip with a float is a nice way to forget how heavy your packs are. The Atigun is the only river in the Refuge that has a road access put-in and take-out. Rafters and kayakers can do a road-to-road segment by launching at the bridge over the Atigun before continuing down the Saginivirtok, which returns to the highway. Perhaps the relative ease of access in relation to other Brooks Range runs has made it possible for some parties to get in over their heads on this section. Compared to the common class II braided character of many of the Brooks Range rivers, the Atigun tumbles through a steeper section of boulder gardens and wall shots as it descends on its eastward course to the Saginivirtok. While the map labels this section as "Atigun Gorge", the river never enters a wall-to-wall canyon, and portaging is possible at river level for those who are comfortable ferrying back and forth in pushy water. At our spring flows around 2700 cfs, it had a fast and powerful feel that would be best suited to class IV paddlers. As water levels drop, the river becomes rocky with plenty of eddies, and others have reported a technical class III run when flows are closer to 1000 cfs.

Hike: Saginivirtok to South Fork Ribdon

Once on the east bank of the "Sag", we began our first hiking segment by heading up a tributary to the southeast. Between the Sag and the South Fork of the Ribdon, there are two scenic passes. The first ascends a twisting drainage before descending along gravel bars to Accomplishment Creek. The travel over the next pass at the head of Accomplishment Creek required ascending a few steeper sections next to some dramatic falls. The lake at the top of the pass was a highlight.

Paddle: South Fork of the Ribdon, II-III (IV)

The uppermost reaches of the South Fork of the Ribdon flow northeast before its confluence with the main stem, where it turns back to the northwest before joining the Sag. While it was unclear how far up this reach would be paddleable, it was floatable right from the base of our descent from Accomplishment Pass. We caught this section at a bankful water level and found the top few miles to be fast and boulder-strewn class III. The river briefly steepens and drops through a short, constricted section surrounded by aufeis that was harder than any other section of the run (IV). Once the river turned north, it consolidated into a fast one-channel slalom around overhanging willow before eventually easing in gradient and difficulty.

Hike: South Fork of the Ribdon to the Upper Ivishak

The longest hiking segment of the route is perhaps the most stunning. Between the Ribdon drainage and the Ivishak, we crossed the continental divide twice as we descended into and out of the Wind drainage by way of two excellent alpine passes. At these high points, scree and talus interrupt the tundra walking, and travel slowed a bit where boulder hopping was required. In the valleys, there's never a shortage of game trails, and we saw hundreds of Caribou in the upper Wind. Early summer travelers should expect some snow travel, including on the descent into the Ivishak valley.

Paddle: Upper Ivishak, I-II

When descending into a drainage from the headwaters, I often fall into the trap of pulling out the boat too early. While the Ivishak has some enchanting little gorges in its upper reaches, it then broadens into a mess of shallow braids, which made us grateful to still be in "hike mode". We ultimately needed to walk downstream to where one more drainage bumped up the flow enough to starfish. Eventually, the river channelizes enough to take some paddle strokes, and it enters a beautiful, broad valley that occasionally cuts through mellow, low-walled canyons. The gravel bar confluence with the "Porcupine Lake drainage" made for a nice transition spot to dry out before the next leg of hiking.

Hike: Upper Ivishak to Marsh Fork of the Canning

Leaving the Ivishak, there are miles of easy gravel bar travel towards Porcupine Lake. Eventually, the gravel bars run out, and what would look to be unpleasant, shrubby walking in a steep, vegetated drainage is aided by excellent game trails. A gradual ascent leads to a stunning pass before a final, steep descent into the Marsh Fork valley. Before transitioning to paddle mode, we walked downstream a mile to where this wide braided section of the Marsh Fork consolidates into a single channel.

Paddle: Marsh Fork of the Canning and Canning Rivers, I-II+

The Marsh Fork of the Canning is one of the better-known rivers in the Refuge, and both private parties and commercial outfitters run this section as a fly-in, fly-out float trip. This uppermost section is above the standard strip used for raft access, and you can expect some starfishing and channel hunting before the river turns north and incorporates a larger tributary. Some of the braided sections of the Marsh Fork have aufeis, a year-round river ice that lines the bank and can create a unique hazard. Eventually, the gradient increases a bit, and the river takes on a more lively class II character that enabled a 45-mile day from our put-in to the confluence with the Canning. While the gradient decreases at the Canning, the increased volume helps the river maintain its pace as it whisks you out of the mountains towards the coastal plain.

Hike: Marsh Fork of the Canning to the Saddlerochit

We transitioned back to hike mode on a gravel bar at the confluence with Eagle Creek. While we planned to hike up Cache Creek, we initially thought hiking on the spit of land between drainages would offer the best travel. We encountered some unexpectedly dense schwacking and quickly bailed to the gravel bars, which proved to be excellent travel all the way to the head of Cache Creek. From the pass, easy tundra walking down Snow Creek and through a low saddle towards Talus Creek made for efficient travel. A clear day should provide awesome views of Mount Chamberlin before you descend to the Saddlerochit.

Paddle: Saddlerochit II-III (III+/IV)

We opted to begin our float on the Saddlerochit, where the river passes through a mini gorge with a fun sequence of ledges (III+/IV). At low flows, the entry falls looked to be a boat ripper, but the other ledges were clean and friendly. At high flow, the uniform character of some of the ledges would make them more retentive and increase the difficulty of this section. The river maintains the canyon character for a few miles with some enjoyable boulder garden rapids before it opens up and becomes less channelized. This middle section was slow and scrapy, but when the Kekiktuk River enters on river right, the flow doubles and the river settles into a splashy and continuous class II character for the remainder.

Hike: Saddlerochit to the Hulahula

Where the Saddlerochit turns north and parallels the Hulahula, only four miles of land separates the rivers. While it's the shortest hiking segment of the trip, it's also a true minefield of tussocks. Luckily, the expansive views of the eastern Brooks Range make the slog more enjoyable.

Paddle: Hulahula, I-II+

The Hulahula is often sought after as a float trip in its own right. While the upper stretch of the river has more whitewater hemmed into a steep and mountainous valley, the lower stretch of the Hula has less gradient as it meanders through the flat coastal plain on its final approach to the Arctic Ocean. While travel slows, the landscape allows for big views of the range and opportunities for wildlife spotting. It's common to be greeted by a cold upstream wind off the ocean, so factor slower travel into your logistics.

Hike: the exit to Barter Island and Polar Bear considerations

The final section of the route includes overland hiking and a few short ferries to reach the Kaktovik Airport on Barter Island. This section of the Arctic coast is polar bear territory, and minimizing our chance of a bear encounter was our primary consideration for our route and timeline of the last day. While polar bears typically live and hunt from sea ice flows, warming temperatures and reduced ice have made it more common to see them on land. This is especially true during the whale harvest in the late summer, when bears can be seen en masse on the beach when they come to shore to feast on carcasses. Given the predatory nature polar bears have shown towards humans, many traveling in polar bear country chose to carry a firearm. Given that only a very small portion of this traverse lies within typical polar bear territory, we opted to bring just flares, air horns, and bear spray to minimize the additional weight, logistics, and safety considerations that come with carrying a firearm. I found this study on the efficacy of bear spray against polar bears to be an interesting read. While the data set is small, it helped me feel more assured in my preference to use a non-lethal deterrent, especially as a recreator willingly putting myself into the territory of an animal facing growing climate stressors. The final route you choose will likely be influenced by the deterrents you bring and your tolerance for risk. Below are some common exit options I ranked from least to most exposed to polar bear encounters.

Inland pick-up: Many of the commonly paddled north slope rivers such as the Canning, Hulahula and Kongakut have inland airstrips that allow for pick-up before hitting the ocean. This option requires a more expensive charter flight, lacks the aesthetic of an ocean finish, but is the safest travel option.

Boat pickup: It is possible to arrange a boat pickup from the mouth of the Okpilak to Kaktovik. I know multiple parties who have arranged this service, but it is expensive. You will still be spending some time in bear territory near the mouth, but less than the remaining options.

Inland Route (shown on the map): This is the option we opted for in 2025. We camped 10 miles inland from the coast on the Hulahula and did a big push all the way to the airport on the last day to minimize time camping near the coast. From near the mouth of the Hulahula, we did a short portage to the Okpilak and ferried across before packing up and beginning our hike. The walking was better than expected, but expect travel to be spongy. There is one more ferry at the end of the route to access Barter Island from the south. This route definitely didn't eliminate bear risk, but it minimized our time in prime bear territory along the coast and seemed like the best option for a trip without chartering a boat or a flight.

Arey Island: Paddle across the lagoon and hike the length of this barrier island before a final ferry to Barter Island. While the travel is reportedly excellent gravel beach walking, the island is a very common spot for bears and also lacks access to fresh water.

Ultimately, what is typical polar bear territory and behavior will continue to shift as their normal patterns are disrupted by warming temperatures. In recent years, there have been a few accounts of bears seen dozens of miles inland, and as such, it is impossible to eliminate polar bear risk along this route.

TRAVEL LOGISTICS

Access: Fairbanks, Alaska, is often the start and end point for many Brooks Range trips. We took the Dalton Highway Express to the start of our route. This 12-passenger van has 3 scheduled trips per week between Fairbanks and the end of the highway in Deadhorse. While the "Express" descriptor may be a stretch, it was nice not to put the mileage and wear on a personal vehicle on the 12-hour-long gravel drive.

Egress: Wright Air offers scheduled service 3 times a week between Kaktovik and Fairbanks. Their hangar in Fairbanks is right next to the Dalton Highway Express pickup point, which makes using these two services in conjunction very convenient. There is a parking lot across the street, which offers long-term parking for $6/day.

Kaktovik: As the primary village with air service on the north slope of the Refuge, Kaktovik has been a common endpoint for packraft traverses in the Refuge. Until recently, Kaktovik was a destination for tourists hoping to see the polar bears that frequent this area of the Arctic Coast. For several reasons, the village asked the BLM to end its bear viewing concession, and since then, Kaktovik has received much less tourist visitation. The two inns that once housed visitors are indefinitely closed, and you should not show up in Kaktovik without a predetermined plan. There are no established campgrounds in town, and the polar bear presence makes camping unsafe. Unless you have sought permission to stay in town or are paying for a prearranged service, I'd recommend just timing your last day of travel to arrive directly at the runway before your flight.

Comments